Introduction

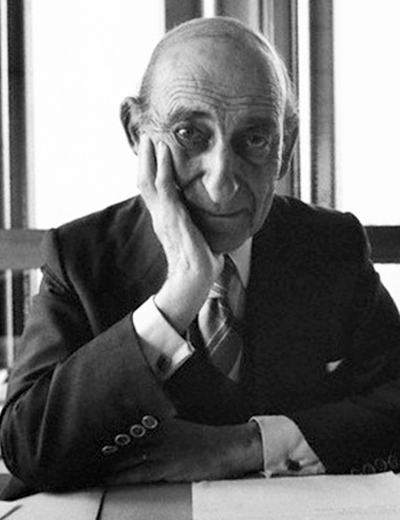

The Committed Observer (Le Spectateur engagé) is one of Raymond Aron’s most popular non-academic works. Published in 1981, it is a series of interviews with Jean-Louis Missika and Dominique Wolton in which he reflects on his fifty years of commentary on political affairs. However, this collection also exemplifies the life and work of Aron himself, who self-consciously succeeds in bridging theory and practice. One might well describe Aron himself as a “committed observer.”

In the tradition of Tocqueville and Montesquieu, Aron’s work combines the life of the mind with a serious engagement with the political and social issues of his day. Eclipsed by the popularity of figures such as Jean Paul Sartre, Simone de Beauvoir, Maurice Merleau-Ponty, and later the neo-Marxists and postmodernists, Aron’s measured opinions often lead him beyond partisan politics. Criticized on both sides of the French political spectrum, Aron refused to sacrifice political prudence for the passionate ideologies of the day.

Aron was one of the most prolific writers of the twentieth century, with over forty books, hundreds of essays, and thousands of newspaper articles to his credit in a fifty-year career. Many of Aron’s theoretical arguments and political judgments were extremely unpopular at the time, although many have been vindicated by subsequent events. In contemporary Europe his work is enjoying a significant revival.

The Opium of the Intellectuals

A socialist in his youth with Kantian philosophic leanings, Aron became disillusioned with Marxism in his student days when he noted how the radical students, despite their pronouncements, were primarily comfortable bourgeois masquerading as revolutionaries. While Aron would become a master interpreter of Marx and Marxism on the theoretical level, his critique characteristically begins from a political or sociological fact that he observes amongst his contemporaries. The movement from theory to practice and back is a feature not only of Aron’s work on Marxism, but his writing on the whole. Aron asks both what is Marxism, but also why Marxism is so appealing to Westerners and later to non-Westerners as well. What is it, Aron wonders, about twentieth-century political life that leads so many intelligent people to justify violence and crime in the service of a political creed?

Aron explores Marx and Marxism throughout his life, but his chief statement on this theme is his 1955 masterpiece, L’Opium des intellectuels, an analysis of Communism and Marxism and their sway over French intellectuals. The title, of course, is a play on Marx’s famous statement that religion is the “opium of the people.” In Aron’s view, Communism is the opium of French intellectuals, who regard a Communist future in quasi-religious terms. According to Aron, in Communism the “proletariat” is cast in the role of a collective savior intended to redeem humanity. Aron painstakingly sketches the various favored ideas of Marxism—not only the proletariat but also the “Revolution” and a universal “Left,” and reveals their mythical character. But Aron also shows that exposing a cherished belief as a myth is not enough to dissuade a believing Communist. For, in the Communist imagination, Communism becomes a kind of secular redemption impervious to empirical refutation.

The book was an important intellectual event in the Cold War, and it helped encourage liberal anti-Communism in France and elsewhere in Europe. But as Harvey Mansfield notes in the introduction to the English translation of the work, this work is not only about the past. “Post-war French intellectuals are not peculiar to France,” Mansfield writes. “[T]hey are the archetype of modern intellectuals everywhere.”

Aron shows that French intellectuals are attracted to Communism because of their undue faith in reason and “theoretical constructs”—such as the Marxist “end-state”—that will resolve all conflict and abolish all politics. They become impatient with imperfection and seek “universalistic” solutions to particular problems. Ironically, says Aron, this leads them to denigrate the actual role that reason can play within politics once the hope of transcending politics is dispensed with. Intellectuals thus swing (sometimes wildly) between extreme faith in reason and fanatical rejection of any reason in favor of the autonomously acting will.

International Relations Theory

Aron calls himself a “realist” by disposition rather than by ideology. Nonetheless, Aron’s work transcends the reductive academic categories of his day (and ours) that speak of foreign affairs in terms of “realism” or “idealism.” Indeed, Aron treats international relations with a characteristically balanced approach of his other domains, arguing that it should not abstract from the praxeology of political actors and their varied motives, as illustrated in Paix et guerre entre les nations (Peace and War), published in 1962. This “Last of the Liberals,” as Allan Bloom later called him, ultimately resists both the idealist call for a Kantian perpetual peace and the vulgarized Thucydidean conception of power politics, opting instead for what Weber calls an “ethics of wisdom.”

Influenced by Tocqueville and Montesquieu, Aron argues that grand causes and particular causes are interwoven. He dismantles the overarching theories of the realist camp of international relations, exemplified by E.H. Carr and Hans Morgenthau, who deemphasize or ignore the particular in favor of one or two main causes such as power or national interest. Restoring the essential connection between international politics and comparative politics, Aron demonstrates how political actors, from Nazi to Communist, are inseparable from larger causes of state behavior. His flexible analysis rejects the popular Marxist interpretations of history and instead takes into account numerous particular variables including power relations, technology, ideology, and foreign policy. Using these variables, Aron resists purely determinist or monistic explanations and a “hypothetico-deductive system in which the relations among the terms or variables would take a mathematical form,” pointing instead to the indeterminacy of diplomatic-strategic behavior, among other unpredictable factors.

In the field of international relations, Aron restores the role of chance and uncertainty in contrast with the undue emphasis placed by his contemporary scholars and practitioners on abstract theories, statistics, or technical know-how. Aron’s framework restores the importance of prudential judgment—statesmanship—in the international realm.

Aron devotes much journalistic and scholarly attention to the question of nuclear weapons and studies how their development both changed and did not change world politics. In his writing of the fifties, Aron resists the idea—popular in Paris as well as Washington—that possession of nuclear weapons could and should lead to an extreme draw-down of conventional forces. Aron correctly foresees the development of the “nuclear taboo” in the international arena. While he does not dismiss the possibility of nuclear war, he notes that no power can be expected to resort to the “ultimate” weapon in response to more minor quarrels in the international realm. The extent of Aron’s direct influence on policy is unclear. Yet by the sixties Aron’s insistence on the importance of conventional forces even in the nuclear era was accepted doctrine in Washington and Paris.

Read More: International Relations, War

Political Sociology

Aron helped restore the French school of political sociology, in the line of Montesquieu, Constant, and Tocqueville, which he defined in his famous Les Étapes de la pensée sociologique (Main Currents in Sociological Thought) as “A school of sociologists that avoid dogmatism, and are interested before all else by the political, which without ignoring social infrastructures, think liberally and give free reign to the political order.” Within this spirit, Aron succeeds in bringing to light, and in some cases fully reviving, various seminal sociological figures and concepts.

Aron’s first book, La Sociologie allemande contemporaine (Contemporary German Sociology), published in 1935, introduced the wider French public to the thought of Max Weber as well as the German sociological tradition on the whole. Along with the philosopher Bertrand de Jouvenel and the historian François Furet, Aron revived the study of Alexis de Tocqueville, a thinker who is now appreciated more than ever on both sides of the Atlantic. In both German sociology and the work of Tocqueville, Aron found an antidote to French political thought, which he sees as too abstract and indeed too philosophic. Aron’s work emphasizes the inseparable link between sociology and history, economics, philosophy, and the political sciences, approaching sociology with the same non-deterministic and interdisciplinary method as his other domains.

Read More: Sociology

Industrial Society

Aron made an important contribution to the framing and popularization of the concept of industrial society within sociology, while always reminding his readers how inseparable the concept was from politics. Among his other works, his trilogy Dix-Huit leçons sur la société industrielle (Eighteen Lectures on Industrial Society) in 1962, La lutte des classes (Class Struggle) in 1964, and Démocratie et totalitarisme (Democracy and Totalitarianism) in 1965 constitutes one of the most definitive treatments of the sociology of industrial society, and the opposition between capitalist and Communist industrial structures. Aron opposes both Heidegger’s condemnation of modern technology and Marx’s historical materialism and rejects the idea of the homogenization of all industrial societies and its supposed spiritually apocalyptic consequences. Aron’s treatment emphasizes factors that were often left out of treatments of industrial society, such as the role of war and regime type. While Aron saw that industrial society posed challenges to society, he thought that technological and industrial progress would not stomp out humanity or opportunities for human flourishing.

Read More: Industrial Society

Jews and Israel

Although Aron was raised in a secular home and always saw himself as a Frenchmen first and foremost, throughout his life he paid much attention to the condition of the Jews and Israel, of which he was always a sympathetic defender. As he aged, Aron devoted more time and reflection to Judaism and the Jews. After De Gaulle made an (infamous) anti-Israel speech during the 1967 Six Day War, Aron analyzed how the clever De Gaulle made political use of old anti-Semitic tropes to further his pro-Arab politics.

Read More: Israel

Influence

With the end of the Cold War, and, particularly, due to the work of a generation of outstanding scholars in France such as Pierre Manent and the late Furet, Aron’s important perspective on politics and international relations has found new audiences. Today, the École des Hautes Études en Sciences Sociales in Paris, for many years Aron’s academic home, hosts the Centre Raymond Aron, which encourages research in “political studies.” If not as influential as it once was, the scholarly-political journal Aron founded in 1978, Commentaire, continues to publish.

Works

The bibliography on this website features only some of Aron’s writing, and focuses particularly on those that have been translated into English. Aron was one of the most prolific writers of the twentieth century, with his essays, books, and articles numbering in the thousands. For those interested, the Centre Raymond Aron features a (nearly) complete bibliography of Aron’s work in French.

–Essays by Glen Feder