Biography

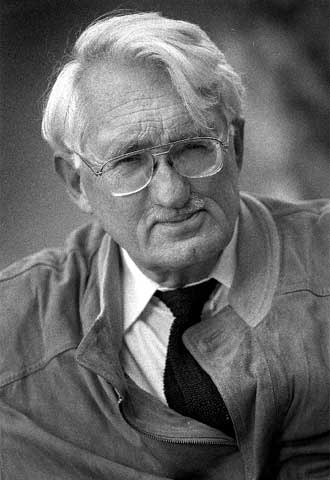

Jürgen Habermas (born June 18, 1929, Düsseldorf, Germany) is widely regarded as one of the most important European philosophers of the second half of the twentieth century, as well as the continent’s leading contemporary public intellectual. A highly influential social and political thinker, Habermas is generally identified with critical social theory, a Marxist inspired movement that emerged in the 1920s at the Institute for Social Research in Frankfurt, Germany—also known as “the Frankfurt School.” Habermas belongs to the second generation of the Frankfurt School, following first-generation and founding figures such as Max Horkheimer, Theodor Adorno, and Herbert Marcuse. Habermas’s theoretical system is devoted to revealing the possibilities of reason, emancipation, and rational-critical communication latent in modern institutions and in the human capacity to deliberate and pursue rational interests—an idea that Habermas popularized as “communicative rationality.”

In addition to his many scholarly contributions, Habermas has embraced the role of a public intellectual. This is reflected in his regular interventions in contemporary European political debates—most prominently with Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger, later Pope Benedict XVI—at the Catholic University of Bavaria in Munich in 2004 on the topic of religion and reason, but also more generally in his writings on the European Union, globalization, and capitalism. In 1986, Habermas received the Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz Prize of the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft, which is the highest honor awarded in German research. He is also the recipient of the Hegel Prize, the Sigmund Freud Prize, the Adorno Prize, and the Geschwister Scholl Prize.

Habermas grew up in Gummersbach, near Düsseldorf, and was a teenager when the wave of Nazi terror overtook his country. After the Nazi defeat in May 1945, he completed his secondary education and attended the Universities of Bonn, Göttingen, and Zürich. At Bonn he received a Ph.D. in philosophy in 1954 with a dissertation on Friedrich von Schelling. From 1956 to 1959 he worked as Theodor Adorno’s first assistant at the Institute for Social Research. Habermas left the institute in 1959 and completed his second doctorate (his habilitation thesis, which qualified him to teach at the university level) in 1961 under the political scientist Wolfgang Abendroth at the University of Marburg; it was published with additions in 1962 as Strukturwandel der Öffentlichkeit (The Structural Transformation of the Public Sphere).

In 1961 Habermas became a “privatdozent” (unsalaried professor and lecturer) in Marburg, and in 1962 he was named extraordinary professor (professor without chair) at the University of Heidelberg. In 1964, strongly supported by Adorno, Habermas returned to Frankfurt to take over Horkheimer’s chair in philosophy and sociology at the Johann Wolfgang Goethe University of Frankfurt am Main (Frankfurt University)—thus effectively becoming the chosen successor of Adorno in the field of critical theory. After 10 years as director of the Max Planck Institute in Starnberg (1971–81), he returned to Frankfurt, where he retired in 1994. Thereafter he taught in the United States at Northwestern University and New York University and lectured worldwide.

As a prominent voice in postwar Germany, Habermas participated in the major intellectual debates in the country. In 1953 he confronted Martin Heidegger over the latter’s rediscovered Nazi sympathies, in a review of Heidegger’s Einführung in die Metaphysik (Introduction to Metaphysics). In the late 1950s, and again in the early 1980s, Habermas engaged with European antinuclear movements, and in the 1960s he was one of the leading theorists of the student movement in Germany. He would eventually break with the radical core of the student movement in 1967, warning against the possibility of a “left fascism.”

In 1977 Habermas protested against curbs on civil liberties in domestic, anti-terrorist legislation, and in 1985–87 he participated in the so-called “historians’ debate” on the nature and extent of German war guilt by denouncing what he regarded as historical revisionism of Germany’s Nazi past; he also warned of the dangers of German nationalism posed by Germany’s reunification in 1989–90. Although he endorsed the Persian Gulf War (1991) as necessary to protect Israel and the bombing of Serbia (1999) by the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) as necessary to prevent the genocide of ethnic Albanians in Kosovo, he opposed the Iraq War (2003).